Problem formulation: How might we catch the challenge that brings new opportunity?

Problem solving and innovation would be much easier tasks if problems would only present themselves fully formed and clearly defined. We’d know exactly what we were trying to achieve, and could leap instantly into finding a solution. In the real world however, no one presents us with problems; to keep ahead of the game, we have to go looking for them. And, no matter how we get them, we’re often facing ambiguous situations where the fuzzy outlines of intertwined problems and opportunities float murkily below the surface. We know that we need to act, but we’re not always exactly sure what we’re attempting to accomplish through those actions.

It was this reality that led Einstein to claim that if he had an hour to solve a problem, he would spend the first 55 minutes defining the problem, and only the last five minutes in action.

It’s highly tempting, particularly for people focused on getting results in today’s fast-paced world, to pull a problem – any problem – out of the murky depths and launch into finding a solution. And in a world of unlimited time and resources, it would probably be a reasonable strategy. If we solved all the problems, eventually we’d be sure to solve a useful one, right? But in our world of finite resources, solving the wrong problems is a distracting task that squanders energy and goodwill.

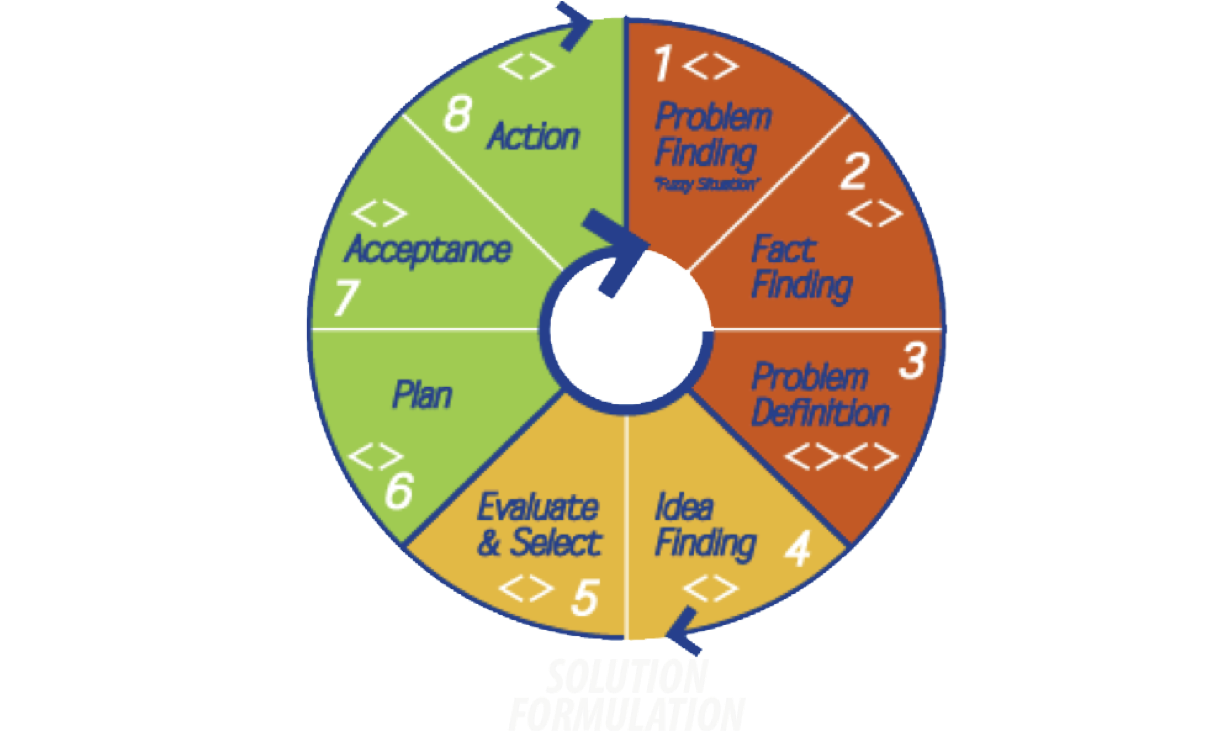

The best way to avoid the pitfall is to follow a clear process through the stages of problem solving. From the fuzzy situation, possible problems are identified, facts are gathered and a final problem is eventually clearly defined – often a breakthrough, out-of-the-box discovery. A range of solution ideas are created/imagined, followed by evaluation and selection of a new optimal solution. Only then does the plan for implementing the solution, promoting its merit and taking action finally occur.

When teams and leaders really understand how the process works, and bring well-developed skills and attitudes to the discussion, the sea of murky choices can yield a catch of outstanding opportunities.